During World War 2, the very first bomb dropped on Berlin by the Allies killed the only elephant in the Berlin Zoo.

During World War II, when the Allies began bombing Berlin, the very first bomb to hit the city caused a quiet but heartbreaking loss far from military targets. That bomb struck the grounds of Berlin Zoological Garden, killing the zoo’s only elephant and marking one of the earliest civilian and animal casualties of the air war over Germany.

The bombing of Berlin began in 1940, when Allied forces started targeting the German capital as part of a broader strategy to disrupt industry, infrastructure, and morale. While the raids were aimed at strategic objectives, early bombing technology lacked precision. As a result, bombs frequently missed their intended targets, landing instead in residential areas, parks and zoos.

The Berlin Zoo, one of the oldest and most prestigious zoological gardens in Europe, lay directly in the path of the city’s expanding wartime footprint. When the bomb fell, it struck the zoo grounds, killing the elephant instantly. The animal had no connection to the war effort, no understanding of the conflict unfolding overhead yet paid the ultimate price.

At the time, elephants were rare and highly valued zoo residents, both for their intelligence and their symbolic appeal. The loss deeply affected zoo staff and Berlin residents alike, many of whom viewed the elephant as a familiar and beloved presence in the city. Newspapers and later historical accounts would reference the incident as a stark example of how war spares no innocents.

As the conflict escalated, the Berlin Zoo would suffer even greater devastation. Repeated air raids over the following years killed or forced the euthanization of many animals, either from bombings, starvation, or the danger they posed if enclosures were destroyed. By the end of the war, the zoo’s animal population had been almost completely wiped out.

Historians often use stories like this to illustrate the psychological and moral toll of aerial warfare. Long before precision-guided munitions existed, bombing campaigns relied on mass attacks that inevitably harmed civilians, cultural institutions, and animals. The elephant’s death became an early reminder of that reality.

The tragedy also highlights a lesser-known aspect of wartime history: the fate of animals caught in human conflicts. Zoos across Europe faced impossible decisions during World War II from relocating animals to killing them preemptively to prevent danger if cages were destroyed. In many cases, animals died without ever being part of the war they were swept into.

After the war, the Berlin Zoo was painstakingly rebuilt, symbolizing resilience and renewal amid the ruins of the city. New animals were acquired, enclosures reconstructed, and life gradually returned. But the memory of those lost, including the elephant killed by the first bomb, remained part of the zoo’s history.

Today, the story stands as a haunting footnote to World War II: proof that the first strike on a great capital city did not hit a factory or a military base, but instead claimed the life of a gentle giant.

It’s a reminder that war’s first victims are often the most voiceless and that even history’s smallest details can carry profound meaning.

There is only one pig (Khanzir) in all of Afghanistan. His name is Khanzir, which is Arabic for pig, and he lives in the Kabul Zoo.

For a time, Afghanistan was home to just one pig, a solitary animal named Khanzir, housed at Kabul Zoo. His name, Khanzir, simply means “pig” in Arabic, and his existence sparked global fascination due to Afghanistan’s cultural and religious context, where pigs are considered unclean in Islam and are not farmed or kept as pets.

Khanzir arrived at Kabul Zoo in the mid-2000s after being gifted from abroad, reportedly as part of an animal exchange. Almost immediately, he became an anomaly not just rare, but singular. Zoo officials and international media outlets widely described him as the only pig in the entire country, a claim that, while difficult to independently verify nationwide, reflected the near-total absence of pigs in Afghanistan.

Because of this, Khanzir became something of a quiet celebrity. Visitors were often surprised to learn that the pig existed at all, let alone in the heart of Kabul. Unlike lions or monkeys, Khanzir’s enclosure drew attention not for spectacle, but for symbolism.

Zoo staff explained that Khanzir was kept primarily for educational purposes and cared for like any other animal. He was not displayed prominently, nor used for provocation. Instead, his presence underscored the Kabul Zoo’s broader mission: to maintain a diverse collection of animals despite years of war, sanctions, and limited resources.

The Kabul Zoo itself has a long and turbulent history. Founded in the 1960s, it suffered immense damage during decades of conflict. Animals were lost to bombing, starvation, and neglect, and staff worked under extreme conditions to keep the zoo operational. Against that backdrop, Khanzir’s survival and uniqueness became even more striking.

International journalists covering Afghanistan often mentioned Khanzir as a curious footnote in stories about the country, using him as an example of how global norms and local traditions can intersect in unexpected ways. He was never controversial locally, but his existence prompted fascination abroad.

Importantly, zoo officials clarified that Khanzir was not meant to challenge religious beliefs. He was simply an animal under human care treated with neutrality rather than judgment. His presence highlighted a core principle of modern zoos: conservation and education transcend cultural discomfort.

Over time, reports about Khanzir faded, and his current status is unclear, especially given political changes and upheaval in Afghanistan. What remains is the story itself one that continues to circulate as a testament to how even a single animal can become symbolic.

Khanzir’s story is not about rebellion or controversy. It’s about rarity, coexistence, and the quiet oddities that survive even in the most difficult circumstances.

In a country shaped by history, faith, and conflict, one pig living quietly in a zoo enclosure became a reminder that the world is full of unexpected details and that sometimes, the smallest stories travel the farthest.

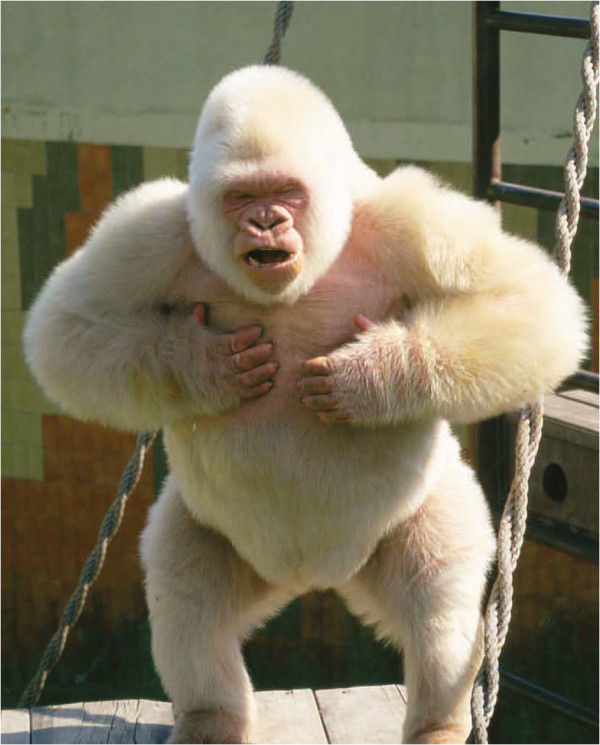

Snowflake is the only known albino gorilla. He was a resident of Barcelona zoo.

Snowflake was a once-in-a-lifetime natural phenomenon the only confirmed albino gorilla ever recorded. With snow-white fur, pale skin, and pinkish eyes, Snowflake stood apart not only from other gorillas, but from every primate ever documented. His existence challenged scientific understanding and captivated the world for nearly four decades.

Snowflake was captured as an infant in Equatorial Guinea in 1966 after his mother was killed by hunters. He was later brought to Europe and became a resident of Barcelona Zoo, where he would live for the rest of his life. From the moment he arrived, it was clear he was extraordinary.

Albinism is an extremely rare genetic condition caused by a lack of melanin, and it is particularly rare among wild animals due to reduced camouflage and increased vulnerability. Snowflake’s survival to infancy in the wild was already remarkable. His survival into adulthood and old age — was extraordinary.

At Barcelona Zoo, Snowflake became an international sensation. Millions of visitors came to see him, and he appeared in documentaries, textbooks, and scientific studies. Researchers were especially interested in his genetics, eyesight, and health, as albinism can be associated with vision problems and increased sensitivity to sunlight.

Despite his uniqueness, Snowflake lived a relatively normal gorilla life. He fathered 22 offspring, none of whom inherited his albinism, confirming that the trait was recessive and extremely rare. Zoo keepers described him as calm and social, though he required special care to protect his skin and eyes from sun exposure.

Snowflakes also played an important role in education and conservation. His fame drew attention to the plight of gorillas in the wild, particularly western lowland gorillas, which face threats from habitat loss, poaching, and disease. For many people, he was their first close encounter even if indirect with a great ape.

In his later years, Snowflake developed skin cancer, a condition linked to albinism and UV sensitivity. In 2003, after his health deteriorated and treatment options were exhausted, veterinarians made the difficult decision to humanely euthanize him at the age of around 38.

His death was mourned worldwide. Newspapers ran tributes, scientists reflected on his significance, and visitors left flowers at the zoo. Snowflake was more than a curiosity; he was a symbol of biodiversity’s unpredictability and fragility.

Today, Snowflake remains a scientific reference point and cultural icon. No other albino gorilla has ever been documented since, making his life truly singular.

Snowflake’s story reminds us that nature occasionally produces miracles rare, fleeting, and unforgettable. And for nearly four decades in Barcelona, the world was lucky enough to meet one.

At the Edinburgh Zoo, there is a voluntary daily penguin parade, which sometimes gets canceled if the penguins do not wish to go out that day.

At Edinburgh Zoo, one of the world’s most beloved animal traditions operates on a surprisingly simple rule: the penguins are in charge. The zoo’s famous daily penguin parade where penguins waddle freely through visitor pathways is completely voluntary. And on days when the penguins aren’t interested, it simply doesn’t happen.

The parade features a colony of king, gentoo, and rockhopper penguins who are given the opportunity to leave their enclosure and explore designated paths within the zoo. Keepers open the gates, step back, and wait. If the penguins come out, the parade begins. If they don’t, that’s the end of it.

No coaxing. No forcing. No disappointment at least not from the staff.

Zoo officials emphasize that the parade is designed around animal welfare and choice, not entertainment. Penguins are naturally curious animals, and many enjoy the stimulation of walking, exploring, and interacting with familiar surroundings outside their enclosure. But just like people, some days they’d rather stay home.

Weather, mood, molting cycles, social dynamics, and individual personality all play a role. Some penguins are enthusiastic regulars. Others prefer to watch from the sidelines. A few might poke their heads out, reconsider, and head back inside a decision that is fully respected.

On those days, keepers simply announce that the penguins have chosen not to parade, and visitors accept it as part of the experience. In fact, many guests find honesty refreshing. The cancellation itself becomes a lesson: animals aren’t performers, and enrichment only works when it’s voluntary.

The tradition began decades ago as a way to provide exercise and mental stimulation. Over time, it became a defining feature of the zoo not because it’s guaranteed, but because it isn’t. The unpredictability reinforces the idea that these are sentient animals with agency, not props in a show.

Animal welfare experts often point to the Edinburgh Zoo parade as a gold standard example of choice-based enrichment. Allowing animals to opt in or out reduces stress and builds trust between animals and caregivers. Penguins that feel safe and unpressured are more likely to engage naturally.

The public response has been overwhelmingly positive. Visitors often cheer whether the parade happens or not, and many say they appreciate seeing animals treated with autonomy. Children, in particular, learn an important lesson: respect means accepting “no” even from penguins.

When the parade does happen, it’s charmingly unpolished. Penguins waddle at their own pace, stop to preen, veer off course, or abruptly change their minds. There’s no choreography, just penguins being penguins.

And when it doesn’t happen? That’s okay too.

The canceled parade has become just as iconic as the parade itself, symbolizing a quiet but powerful philosophy: animal experiences should prioritize consent, not spectacle.

In a world where wildlife is often expected to perform on demand, Edinburgh Zoo’s penguins offer a gentle reminder that sometimes the most respectful thing humans can do is step aside and let animals decide how they spend their day.

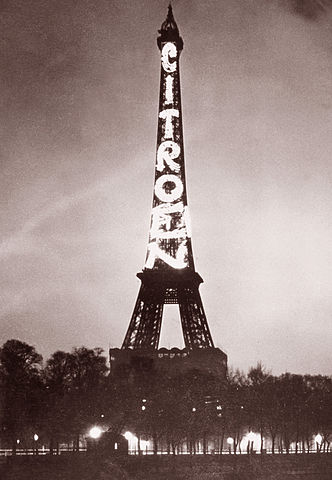

The 1889 World’s Fair in Paris, famous for the construction and unveiling of the Eiffel Tower, had a “Negro Zoo” with 400 black people in cages as one of the attractions.

The Exposition Universelle of 1889 is most famously remembered for introducing the world to the Eiffel Tower, a monument that came to symbolize engineering triumph and modernity. Yet alongside this celebration of progress existed a deeply troubling reality: the fair also featured a “Negro Village,” often described as a human zoo, where hundreds of Black people were exhibited as attractions.

Approximately 400 individuals, primarily from French colonies in Africa, were placed in staged environments designed to depict what organizers falsely portrayed as “primitive” life. They were housed in enclosures, dressed according to European stereotypes, and observed by millions of visitors. The exhibit was presented as educational anthropology but functioned as entertainment rooted in racism and colonial ideology.

This display was not an isolated incident. It was part of a broader 19th-century phenomenon known as human zoos, which appeared across Europe and North America. At the time, pseudo-scientific racial theories were used to justify colonialism, slavery, and imperial domination. Exhibiting colonized people alongside animals reinforced the false narrative that non-European societies were less evolved.

The Paris exhibition took place at the Jardin d’Acclimatation, a venue that had previously hosted similar displays. Organizers framed the exhibit as a celebration of France’s empire, presenting colonized peoples as proof of imperial reach rather than as human beings with dignity and autonomy.

Contemporary accounts reveal that the exhibit was wildly popular. Millions attended, often without questioning the ethics of what they were seeing. Newspapers of the era described the display in objectifying terms, reflecting how normalized such dehumanization had become within mainstream society.

For those exhibited, the experience was one of profound exploitation. They had little control over their conditions, were subjected to constant scrutiny, and were reduced to living symbols of colonial propaganda. Their voices were not recorded in official histories, leaving much of their personal suffering undocumented.

Modern historians now recognize the “Negro Zoo” as a stark example of institutionalized racism embedded within Western ideas of progress. The same fair that celebrated electricity, iron architecture, and industrial innovation also relied on racial hierarchy to define who counted as “civilized.”

The contradiction is striking: while Paris presented itself as the capital of enlightenment, it simultaneously endorsed practices that denied basic humanity to others. This duality has led scholars to reassess world’s fairs not just as celebrations of advancement, but as tools that reinforced global inequality.

Today, the Eiffel Tower remains a global icon, while the human zoo is often omitted from popular retellings of the fair. Yet confronting this history is essential. Remembering the full story honors those who were dehumanized and challenges the idea that progress is ever neutral or universally shared.

The 1889 World’s Fair stands as a reminder that technological achievement does not equal moral progress and that history’s most celebrated moments often carry shadows that must not be forgotten.

MIRACLE SNOW-WHITE PENGUIN DISCOVERED IN AUSTRALIA: A ONE-IN-A-MILLION FIND THAT STUNNED RESCUERS

Wildlife rescuers in Australia were left in awe after discovering an extremely rare snow-white penguin, a sight so uncommon it’s often described as one in a million. The bird’s striking appearance of pure white feathers instead of the typical black-and-white tuxedo immediately caught attention and sparked excitement among conservationists and animal lovers alike.

The penguin was found alone and vulnerable, prompting swift action from local wildlife rescue teams. At first glance, some rescuers reportedly thought the bird was injured or covered in a strange substance. It was only upon closer inspection that they realized they were witnessing something extraordinary: a penguin with a rare genetic condition known as leucism, which causes a partial or complete loss of pigmentation. Unlike albinism, leucistic animals usually retain normal eye color, but their pale coloring makes them stand out dramatically in the wild.

This unusual appearance, while beautiful, can be dangerous. Penguins rely on their dark coloring for camouflage in the ocean black backs blend with deep water when seen from above, and white bellies blend with the bright surface when seen from below. A snow-white penguin lacks this natural protection, making it far more visible to predators both in the water and on land. That vulnerability is one of the reasons rescuers moved quickly to assess the bird’s health.

Veterinary checks showed the penguin was otherwise healthy, though underweight and exhausted, likely due to the challenges of surviving with such rare coloring. Experts believe very few penguins with leucism survive to adulthood in the wild, which makes this discovery even more remarkable. Each confirmed sighting adds valuable knowledge to ongoing research about genetic diversity and survival challenges in penguin populations.

News of the discovery spread rapidly online, with many calling the bird a “miracle penguin” and a symbol of nature’s unpredictability. Conservation groups used the moment to raise awareness about the threats penguins face globally, including climate change, habitat loss, and declining fish stocks. They emphasized that rare genetic wonders like this snow-white penguin highlight why protecting marine ecosystems is so important.

After receiving care, the penguin was placed under close observation, with experts carefully considering the safest outcome whether that means rehabilitation and release or long-term protection. For now, the bird stands as a breathtaking reminder that even in well-studied species, nature can still surprise us.

Source: Wildlife rescue reports and marine conservation experts in Australia

BABY PYGMY HIPPO MOO DENG DOUBLES THAILAND ZOO VISITORS

A tiny bundle of joy named Moo Deng has caused a massive surge in visitors at a zoo in Thailand, with attendance reportedly doubling since the baby pygmy hippo made her public debut. The calf’s name, which translates to “bouncy pork” in Thai, perfectly matches her playful, wiggly personality and the internet can’t get enough of her.

Born at a local zoo, Moo Deng quickly became a viral sensation thanks to her round cheeks, tiny ears, and energetic waddling. Videos and photos of the baby hippo splashing in shallow water, following her mother closely, and squeaking for attention have flooded social media, drawing visitors from across the country and even abroad.

Zoo officials say daily visitor numbers jumped dramatically within days of Moo Deng’s first appearance. Families, tourists, and animal lovers are lining up early just to catch a glimpse of the rare calf during her short public viewing windows. Staff have had to implement crowd-control measures to ensure both visitor safety and the well-being of the young hippo.

Pygmy hippos are classified as endangered, with only a few thousand remaining in the wild, primarily in West Africa. Successful captive births like Moo Deng’s are considered extremely important for conservation and genetic diversity. Zoo veterinarians report that the calf is healthy, feeding well, and showing strong bonding behavior with her mother an excellent sign for her development.

Conservationists are using Moo Deng’s sudden fame as a teachable moment, highlighting the threats pygmy hippos face in the wild, including habitat destruction and poaching. Informational displays near the enclosure explain why protecting wetlands and forests is crucial for the species’ survival.

For many visitors, though, the draw is simple: Moo Deng is irresistibly cute. As one zoo-goer put it, “You don’t just see her, you instantly fall in love.”

Source: Zoo officials and Thai wildlife conservation reports

RARE NEWBORN PYGMY HIPPO NAMED HOLLY BERRY DEBUTS AT TAMPA ZOO

A rare and heart-melting newcomer is stealing the spotlight at ZooTampa at Lowry Park. A newborn pygmy hippopotamus named Holly Berry has officially made her public debut, instantly charming visitors and staff alike with her tiny size, gentle manner, and wobbly steps.

Born just weeks ago, Holly Berry represents a significant win for conservation efforts. Pygmy hippos are classified as endangered, with an estimated population of only a few thousand remaining in the wild, mainly in West Africa. Habitat loss, deforestation, and human encroachment continue to threaten the species, making every successful birth in managed care especially meaningful.

Zoo veterinarians say Holly Berry is thriving. She is nursing well, steadily gaining weight, and staying close to her attentive mother. Unlike their much larger river hippo cousins, pygmy hippos are shy, solitary animals, so early bonding and calm surroundings are critical during the first months of life. Keepers have carefully introduced her to public viewing for limited periods to reduce stress and ensure her healthy development.

The calf’s festive name, Holly Berry, was chosen to reflect both her winter-season arrival and her sweet, joyful presence. Since her debut, the zoo has seen a surge of excitement, with families lining up to catch a glimpse of the tiny hippo splashing in shallow water or napping beside her mom.

Zoo officials hope Holly Berry’s popularity will help raise awareness about pygmy hippo conservation. Educational signage near the habitat explains the challenges these animals face in the wild and how accredited zoos contribute through breeding programs, research, and global conservation partnerships.

For visitors, though, the experience is simple and unforgettable. Seeing Holly Berry’s tiny ears twitch or watching her take careful steps through the water has become a highlight of the zoo proof that even the smallest animals can make a big impact.

Source: ZooTampa at Lowry Park officials and wildlife conservation reports

Leave a Comment