Oldest person ever recorded she smoked for 100 years, drank wine daily, ate nearly 1 kg of chocolate a week, and lived to 122

She broke every rule and every record. Jeanne Calment lived to 122 with cigarettes, wine, and chocolate as lifelong companions.

The title of the oldest person ever reliably documented belongs to Jeanne Calment, a French woman whose extraordinary lifespan continues to fascinate scientists, historians, and the public alike. Born on February 21, 1875, in Arles, France, Calment lived an astonishing 122 years and 164 days, passing away in 1997 a record that remains unmatched and officially recognized.

What makes Jeanne Calment’s story especially compelling is not just how long she lived, but how she lived. Her lifestyle openly contradicted almost every conventional health guideline. She began smoking cigarettes at a young age and continued for nearly a century, reportedly quitting at 117 not for health reasons, but because she could no longer see well enough to light them herself. She also drank wine daily, a habit she maintained throughout adulthood, and famously consumed close to one kilogram of chocolate every week.

Despite these indulgences, Calment retained her sharp wit and independence well into extreme old age. She lived on her own until age 110, moved into a nursing home only after accidentally starting a small fire while cooking, and remained mentally alert for years afterward. When asked about her longevity, she often credited olive oil used generously on her skin and in her diet as well as a sense of humor and emotional detachment from stress.

Calment’s life spanned an almost unimaginable stretch of history. She witnessed the construction of the Eiffel Tower, lived through two World Wars, and once claimed to have met Vincent van Gogh in her youth while he was shopping at her uncle’s store. By the time of her death, she had outlived nearly every person born in the 19th century.

Scientists have studied her case extensively to understand whether her longevity could be replicated or explained. Genetic factors likely played a role in longevity in her family but researchers also point to her resilience, consistent routine, and remarkable stress tolerance. Unlike many long-lived individuals, she did not adhere to strict diets or exercise regimens, though she did enjoy cycling until her 100th birthday and took up fencing in her 80s.

Her story has also fueled debate. Some researchers have questioned aspects of her documentation, though the overwhelming majority of gerontology experts and record-keeping bodies accept her age as authentic, supported by extensive archival evidence including birth, marriage, and census records.

Jeanne Calment ultimately became a symbol of life’s unpredictability. Her habits defied logic, yet her longevity was undeniable. Rather than serving as a prescription for health, her life stands as a reminder that aging is influenced by a complex mix of genetics, environment, mindset, and chance.

She once joked, “I’ve only had one wrinkle, and I’m sitting on it.” At 122, Jeanne Calment didn’t just outlive expectations she rendered them meaningless.

Source:Gerontology Research Group (GRG) age verification records

In 1945, a mother waited at a train station every day, long after the war had ended, hoping her son would still come home.

The war ended but a mother’s waiting did not. Every day, she stood at the station, believing love might outlast loss.

In 1945, as the guns finally fell silent and World War II came to an end, train stations across Europe became places of reunion. Soldiers returned home gaunt but alive, families wept with relief, and crowds gathered in hope. But among those crowds was a mother who kept coming back long after the celebrations faded, waiting for a son who never stepped off the train.

Day after day, she returned to the station. Same platform. Same posture. Same hope. The war was officially over, records had been finalized, and names had been added to lists of the missing and the dead. Still, she waited. For her, the end of the war did not mean the end of possibility.

To outsiders, her vigil looked like denial. To her, it was love refusing to surrender.

She had last seen her son years earlier, when he left in uniform, promising to return. Letters came at first short, censored notes that reassured her he was alive somewhere. Then the letters stopped. No official notice arrived. Nobody. No grave. Just silence. And in that silence, hope survived.

Train stations became symbolic places after the war. They were thresholds between grief and relief, between endings and beginnings. For this mother, the station represented the one place where the impossible could still happen. As long as trains arrived, her son could be on one of them.

People began to recognize her. Railway workers nodded quietly. Commuters whispered. Some pitied her, others admired her devotion. No one had the heart to tell her to stop. Because how do you tell a mother that hope has expired?

Psychologists later described this kind of waiting as “ambiguous loss” a grief without closure. When there is no body, no confirmation, the mind refuses to complete the mourning process. Letting go feels like betrayal. Waiting feels like loyalty.

Years earlier, she had waited for him to come home from school. Later, from his first job. Waiting had always ended with relief. Why should this time be different?

As months passed, fewer soldiers returned. The crowds thinned. But she remained. The war had taken her son, but she would not let it take her faith in his return. Each train that arrived carried a small, flickering possibility and she clung to it.

Her story was never recorded in official history books. No monument bears her name. Yet her quiet vigil represents thousands of parents who lived with unanswered questions after the war. Mothers and fathers who never received certainty, only absence.

Eventually, the station changed. Trains modernized. Schedules shifted. Time moves forward, as it always does. Whether she ever stopped coming is unknown. But what she left behind was a haunting truth: wars do not end when treaties are signed. They end slowly, unevenly, inside the hearts of those who wait.

And sometimes, they never truly end at all.

She accused the President of fathering her child in a 1927 book. Branded a liar until DNA proved her right 92 years later.

She told her truth in ink and paid for it with her reputation. Nearly a century later, science proved the world was wrong.

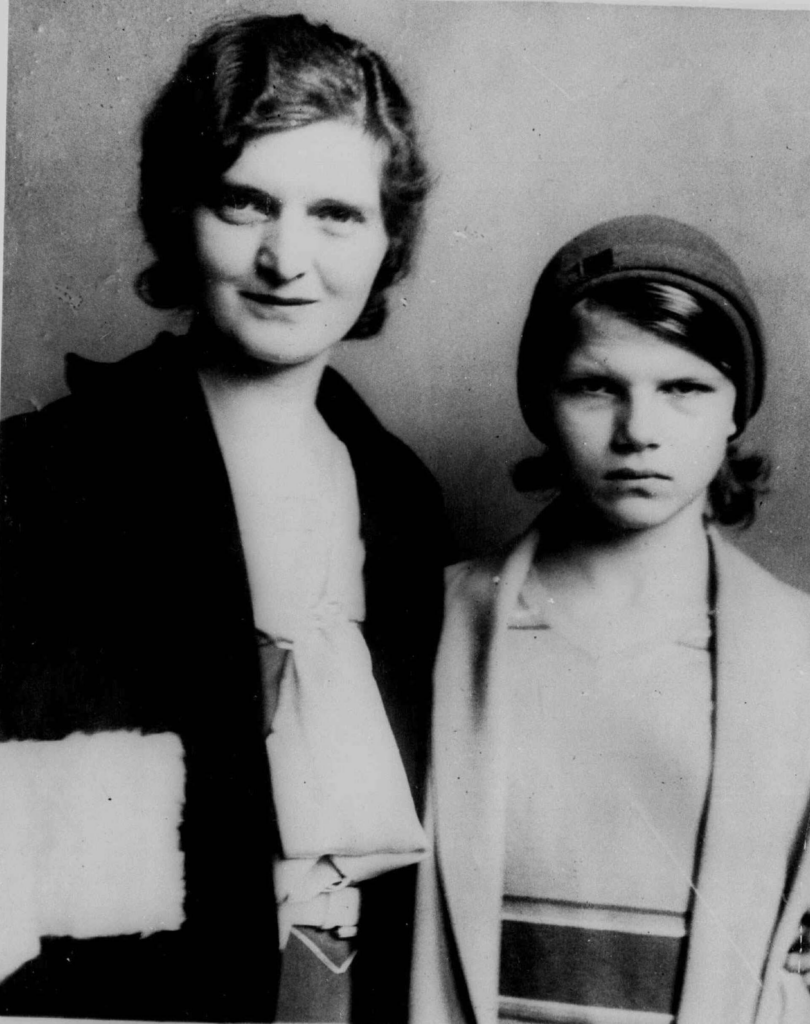

In 1927, a young woman named Nan Britton did something almost unthinkable for her time: she published a book accusing a sitting U.S. president of fathering her child. The president was Warren G. Harding, and the claim detonated across American society. The book, The President’s Daughter, was met with ridicule, outrage, and near-universal disbelief. Britton was labeled a liar, a gold-digger, and a disgraced woman seeking attention.

For decades, history sided against her.

Nan Britton alleged that she had carried on a secret affair with Harding beginning when she was just 20 years old and he was a powerful senator and later president. She claimed the relationship continued into his presidency and resulted in the birth of a daughter, Elizabeth Ann Blaesing, in 1919. According to Britton, Harding supported the child financially through intermediaries but never publicly acknowledged her.

At the time, her accusation was scandalous beyond measure. A single mother accusing the president without physical proof stood little chance against political machinery, gender bias, and public morality. Harding’s supporters fiercely denied the claim, and after his death in 1923, his family worked aggressively to protect his legacy. Britton’s book was dismissed as sensational fiction, and she was effectively erased from respectable public discourse.

She died in 1991, never vindicated.

But history has a way of circling back.

In 2015 ninety-two years after Harding’s death modern DNA testing finally answered the question that had haunted Britton’s life. Genetic analysis conducted between Elizabeth Ann Blaesing’s descendants and members of the Harding family revealed an overwhelming match. The results conclusively proved that Warren G. Harding was, in fact, Elizabeth’s biological father.

Nan Britton had been telling the truth all along.

The revelation sent shockwaves through historical and political circles. What was once dismissed as scandal was suddenly reframed as a story of silencing, power imbalance, and institutional denial. Britton, long portrayed as unreliable, emerged as a woman who had dared to speak against one of the most powerful men in the country and paid the ultimate social price for it.

The case also forced a reevaluation of how women’s testimonies have been treated throughout history. Lacking DNA evidence, legal recourse, or societal support, Britton had little more than her word and in the 1920s, that was not enough. Her truth survived not because she was believed, but because it was recorded.

Today, her story stands as a reminder that truth does not always arrive on time. Sometimes it waits for science, for perspective, for a future willing to listen.

Nan Britton never lived to see her name cleared. But nearly a century later, history finally caught up with her courage.

Source:DNA testing results reported by the Harding family (2015)

They stripped her Medal of Honor in 1917.She refused to return it, wore it daily until her death and 58 years later, it was restored. She was right all along.

They tried to erase her honor and she wore it anyway. Mary Edwards Walker never gave back what she earned, and history eventually agreed.

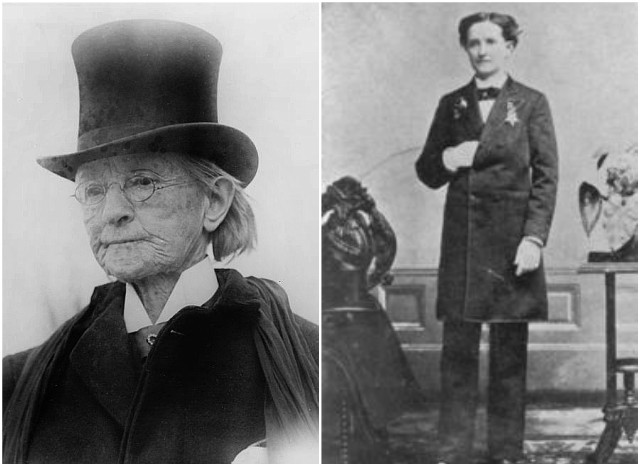

In 1917, the U.S. government made a decision that would stand for decades as one of the most controversial reversals of military recognition in American history. Mary Edwards Walker, a pioneering physician and Civil War hero, was stripped of the Medal of Honor she had been awarded more than 50 years earlier. Officials claimed she no longer met revised eligibility standards. Walker’s response was simple and defiant: she refused to return it.

And she never did.

Mary Edwards Walker was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1865 for her extraordinary service during the American Civil War. As a trained surgeon at a time when women were largely barred from the profession she volunteered her skills to treat wounded soldiers on the front lines. When denied official status due to her gender, she worked as a civilian surgeon anyway, often crossing enemy lines to care for the injured. In 1864, she was captured by Confederate forces and held as a prisoner of war for four months before being exchanged.

Her bravery was undeniable, but her very existence challenged the norms of her era. Walker wore men’s clothing, rejected restrictive fashion, and openly defied gender expectations. To many contemporaries, she was as unsettling as she was impressive.

In 1917, amid a sweeping review of Medal of Honor recipients, the government retroactively revoked awards from 911 individuals, including Walker. The rationale was technical: she had not been a commissioned officer. But the message was unmistakable: her contributions were being reinterpreted through a lens that excluded women by design.

Walker was in her 80s at the time. She was told to surrender her medal.

She refused.

Instead, she wore it every day, pinned to her tailored men’s suit, a visible act of protest and conviction. To Walker, the medal was not a symbol granted by bureaucracy—it was proof of service, sacrifice, and truth. Taking it off would have meant admitting she was wrong. She never did.

Mary Edwards Walker died in 1919, still wearing her Medal of Honor, officially disgraced in the eyes of the government but unwavering in her belief that history would vindicate her.

It took 58 years.

In 1977, after renewed examination and growing recognition of her role as both a war hero and a trailblazer for women, President Jimmy Carter restored her Medal of Honor. The revocation was acknowledged as unjust. Walker became and remains the only woman in U.S. history to hold the Medal of Honor.

The restoration didn’t just correct a record; it affirmed a truth Walker had lived by long before official recognition returned. She had earned that medal through courage, skill, and sacrifice, regardless of whether institutions were ready to acknowledge it.

Mary Edwards Walker was right all along. She didn’t wait for validation. She wore the truth until history caught up.

Source:U.S. Army Center of Military History

She listened to the last man who spoke his people’s language dying and taking 3,000 years of history with him unless she wrote fast enough.

One dying voice. Three thousand years of memory. History survived only if her pen could outrun time.

She sat across from a man the world had already failed.

He was the last person on Earth who could speak his people’s language, a language shaped by nearly 3,000 years of stories, songs, rituals, and knowledge. His name was Ishi, and when he spoke, he carried an entire civilization in his voice. But he was dying. And unless someone could write fast enough, everything he knew would disappear with him.

Ishi emerged from the forests of Northern California in 1911, alone and starving, after decades of violent displacement that wiped out the Yahi people. When he walked into the modern world, he became known as “the last wild Indian,” a label that reflected more about society’s cruelty than his reality. What he truly was, though, was the final living archive of a culture that had survived millennia until it didn’t.

Anthropologists and linguists quickly realized the urgency of his existence. The Yahi language had never been fully written down. No textbooks. No recordings. No dictionaries. Only memory. And that memory was now confined to one fragile human body weakened by disease.

So they listened.

Day after day, a linguist sat with Ishi, asking him to name objects, describe customs, tell stories, and explain grammar structures that had never been translated before. Every sound mattered. Every pause mattered. The work was painstaking and relentless. If she missed a word, it might be gone forever.

Languages are not just vocabulary, they are ways of seeing the world. In Yahi, words encoded relationships with animals, land, and seasons in ways English could not easily replicate. Concepts that had guided survival for thousands of years now depended on whether someone could hear, understand, and transcribe them accurately before time ran out.

Ishi, for his part, gave everything he could. Despite the unimaginable loss his family killed, his people erased, he shared his knowledge patiently, even generously. He knew what was at stake. Teaching was a final act of resistance against disappearance.

In 1916, Ishi died of tuberculosis.

But the language did not die with him.

Because someone had written fast enough.

Thanks to those frantic notes, later scholars were able to reconstruct parts of the Yahi language, preserving its sounds, structure, and meaning for future generations. While the culture could never be fully restored, it was not entirely lost to silence.

This moment stands as one of the most fragile points in human history where thousands of years are balanced on the breath of one man and the speed of one listener’s pen. It reminds us that languages don’t vanish suddenly. They fade when no one is left to hear them.

And sometimes, survival depends not on armies or monuments but on listening closely, and writing everything down before the last voice goes quiet.

Source:University of California anthropological archives

“Women who think critically are always labeled difficult because it saves the world from admitting they’re right.”- bell hooks

Truth-tellers are rarely rewarded with comfort. Bell hooks remind us that calling women “difficult” is often a way of dodging their truth.

The words of bell hooks continue to resonate because they articulate a social pattern that spans generations, cultures, and institutions. Her quote “Women who think critically are always labeled difficult because it saves the world from admitting they’re right” is not merely an observation; it is an indictment of how power protects itself.

At the heart of the statement lies a simple but uncomfortable truth: critical thinking threatens entrenched systems. When women question authority, challenge norms, or expose contradictions, the response is rarely an honest engagement with their ideas. Instead, attention shifts to their demeanor. They are described as “difficult,” “aggressive,” “intimidating,” or “too much.” These labels function as social shields, allowing institutions and individuals to dismiss insight without confronting its implications.

bell hooks spent her career examining how patriarchy, racism, capitalism, and sexism intersect to silence marginalized voices. She understood that the marginalization of women’s intellect is not accidental, but structural. Labeling women as “difficult” reframes intellectual resistance as a personality flaw. It suggests the problem lies not in the injustice being named, but in the woman daring to name it.

This dynamic is especially pronounced for women of color, whose hooks are centered throughout her work. Their critical perspectives are often met with heightened scrutiny and harsher penalties. Where confidence in men is rewarded as leadership, the same behavior in women is reframed as hostility. The effect is chilling: self-censorship becomes a survival strategy.

The quote also reveals how society prioritizes comfort over truth. Admitting that a woman is right may require reevaluating long-held beliefs, redistributing power, or acknowledging complicity. Labeling her “difficult” is easier. It preserves the illusion that existing systems are fair and functional, while casting dissent as disruption rather than necessary correction.

Importantly, hooks does not frame this as a personal failure women must overcome by softening themselves. She rejects the idea that women need to be more palatable to be heard. Instead, her work insists that discomfort is often the first sign of meaningful learning. Growth, she argues, does not come from ease it comes from confrontation with ideas that unsettle us.

For many readers, this quote becomes a mirror. Women recognize moments when they were sidelined not because their arguments lacked merit, but because they challenged authority too directly. In that recognition lies both validation and empowerment. Being labeled “difficult” may not be a mark of failure, but evidence of intellectual integrity.

Bell hooks’ legacy lies in her ability to make theory accessible while never diluting its rigor. Her words continue to circulate because they name lived experience with precision. Decades after she first articulated these ideas, the pattern remains visible making her insight not dated, but urgently current.

To sit with this quote is to confront a choice: dismiss critical women as problems, or accept that they may be pointing toward truths we are reluctant to face.

Source:bell hooks, Feminism Is for Everybody

If the system were fair, women wouldn’t be told to wait patiently for equality.”- Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Equality delayed is inequality defended. Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s words remind us that justice was never meant to be patient.

Few figures in modern history have articulated the quiet injustices of inequality as precisely as Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Her statement “If the system were fair, women wouldn’t be told to wait patiently for equality” cuts through decades of polite deflection with unmistakable clarity. It exposes a truth that generations of women have lived: calls for patience are rarely neutral. They are tools of delay.

Throughout her career as a lawyer, judge, and Supreme Court justice, Ginsburg encountered this logic repeatedly. Women were told progress was coming just not yet. That equality required time, adjustment, and restraint. But Ginsburg understood something essential: justice that requires endless waiting is not justice at all. It is postponement disguised as reasonableness.

The phrase “wait patiently” is doing heavy work in her quote. It implies that inequality is an inconvenience rather than a violation. It shifts responsibility away from systems that benefit from imbalance and places it onto those harmed by it, asking them to be calm, grateful, and non-disruptive while their rights remain incomplete. Ginsburg rejected that framing outright.

Her legal strategy reflected this belief. Rather than arguing only for women’s rights, she challenged gender discrimination as a constitutional issue that harmed everyone. By representing male plaintiffs in early gender-equality cases, she revealed how laws rooted in gender roles limited opportunity across society. The system wasn’t merely slow—it was structurally biased.

What makes this quote endure is how widely it applies beyond the courtroom. In workplaces, politics, education, and culture, marginalized groups are often told that progress takes time, that pushing too hard risks backlash. Ginsburg’s words call out the imbalance in that demand. Those who benefit from delay rarely bear its cost.

Importantly, her critique was never about impatience for its own sake. Ginsburg was known for her measured tone, meticulous reasoning, and respect for institutions. But restraint did not mean acceptance. She understood that progress required pressure—and that pressure was often labeled unreasonable by those comfortable with the status quo.

The quote also reflects her broader philosophy: equality should not depend on endurance. No group should have to prove their worth by waiting quietly while others enjoy full rights. The fairness of a system can be measured by whether it demands patience only from those it disadvantages.

In today’s conversations about gender equality, reproductive rights, pay equity, and representation, Ginsburg’s words feel strikingly current. The language of delay persists. So does the expectation that women should be patient, flexible, and understanding in the face of systemic barriers.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg did not ask women to wait. She asked the law and the country to do better. Her legacy reminds us that equality is not a future favor to be granted. It is a present obligation.

Source:Ruth Bader Ginsburg, public speeches and judicial writings

Alma Karlin traveled the world with a typewriter and one suitcase Now her city honors the woman it once feared

She crossed continents with a typewriter and courage. Now Celje honors Alma Karlin, the woman it once misunderstood.

Long before solo female travel was normalized or even tolerated, Alma Karlin set out to explore the world alone, armed with little more than a typewriter, a suitcase, and an unshakable belief in her own independence. In the early 20th century, her journey defied every expectation placed on women. Today, the very city that once viewed her with suspicion now celebrates her as one of its most extraordinary daughters.

Born in 1889 in Celje, Karlin grew up intellectually gifted but socially out of step. She spoke multiple languages, rejected traditional domestic roles, and was openly uninterested in marriage choices that marked her as “difficult” and unconventional in her hometown. Rather than conform, she left.

In 1919, just after World War I, Alma Karlin began an eight-year journey around the globe. Traveling alone through South America, Asia, Oceania, and beyond, she supported herself by writing, translating, and teaching languages. Her typewriter was her livelihood. Her suitcase held everything she owned. She navigated foreign cultures, colonial systems, illness, poverty, and constant danger often as the only European woman traveling without male protection.

Her experiences became books, essays, and travelogues that gained international readership, particularly in Germany. Karlin wrote vividly about cultures she encountered, often with curiosity and empathy unusual for her time. Yet her independence came at a cost. Back home, she was seen as unsettling. A woman who refused domestic life, traveled alone, and spoke openly about the world did not fit neatly into early 20th-century social norms.

During the rise of fascism, Karlin’s life became even more precarious. She openly opposed Nazism, which led to her imprisonment during World War II and eventual exile. After the war, impoverished and in declining health, she returned to Celje but not to celebrate. She lived quietly and died in 1950, largely overlooked and misunderstood.

Decades later, perspectives shifted.

As conversations around feminism, decolonization, and women’s history evolved, Alma Karlin’s life was reevaluated. Scholars recognized her not only as a traveler, but as a pioneering ethnographer, polyglot, and chronicler of global cultures. Her refusal to conform was no longer seen as defiance but as vision.

Today, Celje honors her legacy. Museums, exhibitions, statues, and cultural programs now bear her name. The city that once feared her independence has embraced it, recognizing that Karlin was never out of place; she was simply ahead of her time.

Alma Karlin’s story reminds us how often societies misjudge those who move beyond accepted boundaries. Her life was proof that curiosity is not disloyalty, independence is not selfishness, and courage often looks like disobedience before it looks like legacy.

She traveled the world with a typewriter and one suitcase. What she carried back changed how history remembers her.

Source:Celje Regional Museum archives

Leave a Comment